The Living Transitionals Part I

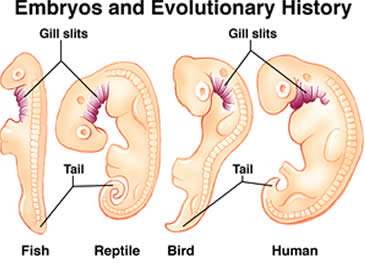

Ever wanted to see a living transitional? There are many creatures today that give insights into possible evolutionary pathways of the past. There are creatures today evolving in the same way that many of their relatives did so long ago. For example, the snake evolved from lizards (by losing its legs) and today we have lizards who found it advantageous to shed the legs. There are mammals like the duck-billed platypus and echidna, who have held on to reptilian traits such as laying eggs. The walking catfish's habitats are "Warm, stagnant, often hypoxic waters such as muddy ponds, canals, ditches, swamps and flooded prairies." This is exactly the sort of environment created by droughts during the Devonian, leading to amphibians and later to reptiles. Watch it walk here.

There's the flying squirrel, who illustrates a path for the evolution of flight. Who knows? In a million years it could be like a mammalian bird.

Posted by

AIGBusted

at

12:35 AM

0

comments

![]()

Velociraptor had feathers

Tiny bumps on the fossilized arm bone of a Velociraptor specimen show that the carnivorous dinosaur — made infamous in the movie "Jurassic Park" — had feathers.

The finding, detailed in the Sept. 21 issue of the journal Science, confirms what scientists have long suspected about the creature as fossils of some of its close relatives bear imprints of feathers.

The researchers believe the bumps on the arm bone are remnants of quill knobs, places where the quills of secondary feathers — important for flight in many modern birds — were anchored to the bone.

"Finding quill knobs on Velociraptor means that it definitely had feathers," said study team member Alan Turner, a paleontology graduate student at the American Museum of Natural History and at Columbia University in New York. "This is something we'd long suspected, but no one had been able to prove."

Not for all birds

Quill knobs are most evident in modern birds that are strong flyers, such as falcons and hawks. Birds that have lost the ability to fly or that primarily soar, like broad-winged albatrosses, typically lack quill knobs.

While studying the forearm of a Velociraptor specimen unearthed in Mongolia in 1998, the researchers noticed six regularly spaced indentations in the fossilized bone that appeared remarkably similar to the quill knobs of modern birds.

In modern birds, secondary feathers are connected to the forearm by way of ligaments. When the feathers move, they place stress on the bone. “The bones respond to the tug of the feathers by developing these little bumps,” Turner explained. “The quill knobs are a side effect of how the feathers anchor.”

Velociraptor lived during the late Cretaceous Period about 85 million years ago and belonged to a group of agile, bipedal dinosaurs called Dromaesoaurs that were closely related to birds. It was roughly the size of a turkey and weighed about 30 pounds.

A prehistoric turkey

Despite having feathers, Velociraptor could not fly or even glide, Turner said.

“Even though it had really long arms compared to most carnivorous dinosaurs, they’re not long enough compared to the rest of its body,” Turner told LiveScience.

The researchers suggest that an ancestor of Velociraptor might have lost the ability to fly but retained its feathers anyway. The feathers might also have been used for display, to shield nests, for temperature control or to help the dinosaur maneuver while running.

The new finding is just the latest example of how remarkably alike modern day birds and their closely related dinosaur ancestors were, said study team member Mark Norell, a curator in the AMNH’s Division of Paleontology.

“Both have wishbones, brooded their nests, possess hollow bones and were covered in feathers,” Norell said. "If animals like Velociraptor were alive today our first impression would be that they were just very unusual looking birds."

Posted by

AIGBusted

at

6:51 PM

3

comments

![]()

The 'Hobbit' wasn't quite human

U.S. scientists, wringing their hands over the identity of the famed "hobbit" fossil, have found a new clue in the wrist.

Since the discovery of the bones in Indonesia in 2003, researchers have wrangled over whether the find was an ancient human ancestor or simply a modern human suffering from a genetic disorder.

Now, a study of the bones in the creature's left wrist lends weight to the human ancestor theory, according to a report in Friday's issue of the journal Science.

The wrist bones of the 3-foot-tall (0.91 meter) creature, technically known as Homo floresiensis, are basically indistinguishable from an African ape or early hominin-like wrist and nothing at all like that seen in modern humans and Neanderthals, according to the research team led by Matthew W. Tocheri of the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History.

That indicates that it is an early hominin and not a modern human with a physical disorder, they contend.

"It seals the deal," Tocheri said in a telephone interview.

The specimen he studied lived on the Indonesian island of Flores about 18,000 years ago, a time when early modern humans populated Australia and other nearby areas.

Scientists had thought humans had the planet to ourselves since Neanderthals died out about 30,000 years ago, and the discovery of Hobbits indicates another evolutionary cousin who coexisted longer, Tocheri said.

It is not known whether humans and Hobbits coexisted on that island, he said, but it is clear we shared the planet for some time.

"Basically, the wrist evidence tells us that modern humans and Neanderthals share an evolutionary grandparent that the hobbits do not, but all three share an evolutionary great-grandparent. If you think of modern humans and Neanderthals as being first cousins, then the hobbit is more like a second cousin to both," Tocheri said.

When the bones were first discovered some scientists declared them the remains of a new, dwarf species of human ancestors. Because of its tiny stature it was quickly dubbed the "Hobbit," from the creature in the books by J.R.R. Tolkien.

Dean Falk of Florida State University said the new report helps confirm that conclusion.

"This is exciting and should help settle things," she said. "The authors are to be congratulated, not only for describing important new details about 'Hobbit,' but for shedding light on the evolution of the wrist and how it might have related to tool production."

But others have questioned whether it was really a new species. Robert D. Martin of the Field Museum in Chicago and co-authors challenged the original classification, arguing that it appears to be a modern human suffering from microencephaly, a genetic disorder that results in small brain size and other defects.

There are things that can go wrong in the development of the wrist, Tocheri said, but they do not result in a complete change of design from modern human to chimpanzee or gorilla wrist.

Nonetheless, Martin said he is standing by his position.

"My take is that the brain size of (that specimen) is simply too small. That problem remains unanswered," he said in a telephone interview.

"People ask me whether this new evidence changes anything, well it doesn't," he said. "I think the evidence they've presented is fine, it's the interpretation that is problematic."

Source:

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/20893732/?gt1=10357

The Hobbit is pictured in the center

Posted by

AIGBusted

at

6:43 PM

0

comments

![]()

1.8 million year old hominids discovered

Paleontologists are examining the partial skeletons of a group of four individuals who died in what is now the Republic of Georgia nearly 1.8 million years ago.

Their remains -- the earliest members of the Homo genus found to date outside of Africa -- are telling much about how key body changes propelled this group's spread around the planet.

"Their lower extremities are evolving faster than their brain and upper extremities, and that seems to be what's necessary for taking them out of Africa and on a long trip to other parts of the world," explained anthropologist Jeffrey Laitman, director of anatomy at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, in New York City.

According to the fossil record, mankind's ancestors arose from the first true bipeds, called australopiths, of which 3-million-year-old "Lucy" is an early member. They then went on to develop the larger brain capacity and more upright gait that characterizes the genus Homo, to which modern humans belong.

In Africa, the Homo genus included first Homo habilis and then the larger-brained Homo erectus. Both were increasingly comfortable walking upright on land over long distances.

In the early 1990s, scientists digging in Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia (between Turkey and Russia), came upon a remarkable find: The skull specimens of early Homo individuals dating to 1.77 million years ago. "When they were first described, it was really quite revolutionary to see material [like this] out of Africa," Laitman said.

The time period in which the four Dmanisi individuals -- three adults and one adolescent -- lived is called the Plio-Pleistocene age. "It's right around the time that we have the emergence and spread of the earliest members of the genus Homo," said Erik Trinkaus, a professor of physical anthropology at Washington University in St. Louis.

Members of the Homo genus gradually spread north and east of Africa beginning (as far as scientists can tell) about 1.8 million years ago. They spread relatively quickly, reaching Southeast Asia and Indonesia by 1.5 million years ago, Trinkaus noted.

And, according to the Dmanisi remains, their more human-like legs and feet may have helped get them there.

"Absolute hindlimb length of the Dmanisi hominins is greater than in australopiths and close to that of later Homo, including modern humans," wrote the Georgia team, which was led by David Lordkipanidze of the Georgian National Museum in Tbilisi. "This may reflect selection for improved locomotor energy efficiency," they explained.

Laitman agreed that it's no coincidence that Homo's spread was linked to their improved bipedal gait. The specimens "also show features of the transverse arch of the foot, the longitudinal arc of the foot, and a particular [movement] of the big toe" not seen before, he said.

And yet other parts of the specimens' skeletons lagged behind in terms of approximating modern humans. For example, their upper limbs fit into the Homo genus but retained some characteristics of australopiths, the researchers noted. The Dmanisi group was relatively small-statured, too -- about 5 feet tall and 100 pounds on average.

Most significant, their brains were only 600 to 775 cubic centimeters in volume -- less than half that of modern Homo sapiens.

To Laitman, all of this means that, "If you were going to go on a long trip, you didn't have to be a genius -- but you did need good feet."

This "mosaic" of features -- some more human-like than others -- means the Georgia researchers have been careful not to give their skeletons a specific taxonomic label, such as Homo habilis or erectus. "You're not yet having anyone saying which drawer in the museum desk these bones should be placed in," Laitman noted.

Source:

http://www.livescience.com/healthday/608351.html

Posted by

AIGBusted

at

6:25 PM

1 comments

![]()

How Brown Evolved into Black

Perry Marshall has challenged evolutionists to show how it is possible to evolve the word Brown into the word Black without ending up with a nonsensical word.

I have accepted his challenge and will show how it is possible using only the sorts of mutations observed in nature.

1. Brown

2. Blown

A mutation causes the 'r' to change into 'l'

3. Block

A double mutation causes the 'w' and 'n' to become 'c' and 'k'

Double mutations have been observed to occur.

4. Black

The letter 'o' becomes 'a'

Now, keep in mind that this would not happen in his random mutation generator because it uses only muation instead of natural selection. It does not take into account the fact that mutations can become fixed in a population, nor that bad mutations are 'filtered out' by natural selection. It also does not recognize that words are different from DNA since DNA uses 4 letters while our alphabet is composed of 26 letters.

Posted by

AIGBusted

at

3:55 PM

3

comments

![]()

Endogenous Retroviruses Prove Evolution Beyond a Reasonable Doubt

I will begin this essay by quoting the intelligent design blog Uncommon Descent:

"Endogenous retroviruses are molecular remnants of a

past parasitic viral infection. Occasionally, copies

of a retrovirus genome are found in its host’s genome,

and these retroviral gene copies are called endogenous

retroviral sequences. Retroviruses (like the AIDS

virus or HTLV1, which causes a form of leukemia) make

a DNA copy of their own viral genome and insert it

into their host’s genome. If this happens to a germ

line cell (i.e. the sperm or egg cells) the retroviral

DNA will be inherited by descendants of the host.

Again, this process is rare and fairly random, so

finding retrogenes in identical chromosomal positions

of two different species indicates common ancestry."

So let's review: On a rare occasion a virus will

insert itself into it's host's genome at random, and

the host's descendants will inherit this and have the

virus in their genome. Our genome is 3 billion base

pairs, so it is extremely unlikely that any creature

would share the exact same virus in the exact same

place in the genome. But yet humans and primates do

have the same viruses in the same places in their

genome.

This article was written by Douglas Theobald, the

assistant professor of biochemistry at Brandis

University.

In order to prove this truly is evidence of evolution,

let me consider the following questions:

(Some of this information was obtained from the Endogenous Retrovirus blog)

1. Is the viral insertion really random?

Yes. Here are two papers creationists use in support

of the nonrandom viral insertion hypothesis:

http://biology.plosjournals.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0020234&ct=1

http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/158/2/769

The first paper simply states that some retroviruses

like to insert in genes, some like to insert near

promoters of genes, and some like to insert in the

middle of no where. The specific insertion sites, what

base pairs on on the left, which ones are on the

right, is random. Thats exactly what they looked for

in that papers methods.

In the second paper the researchers found two

independent Viral insertions in deer mice. They could

tell the insertions apart because the virus had

infected two different places, because this event

happened twice.

So Retroviral insertion is indeed random.

2. Do the Viruses serve any good purpose?

No. When ERV's do become functional, they cause

disease:

http://www.arthritis.arizona.edu/HERV.htm

http://www.mylonglife.com/articles/Retroviruses_Aids_Cancer_And_Autoimmune_Diseases.htm

In closing, you can google "endogenous retrovirus" and

pull up plenty of medical, scientific, and educational

websites. If you email the website, they will tell you

the exact same thing I am. You could also visit a

university and contact a geneticist who will provide

you with the same information.

Posted by

AIGBusted

at

2:58 PM

38

comments

![]()